Grandy and the Lapagator

De Natura Hominis Oeconomici (On the Nature of the Economic Man)

The homo economicus. Latin for “economic man.”

After we’ve walked through a little dust and sweat and motor oil, after we’ve stood in the shop where I first learned what work smelled like, we’ll get back to that Texas tongue-twister Latin word.

Before you can understand what an economic man is, you’ve got to meet my grandfather, Grandy.

He was one of those West Texas men who came from the old soil, hands like bark, heart like flint, and a will as steady as a sunrise. He worked his day job, came home, and went straight to the shop behind the house.

He fixed tractors for half the city.

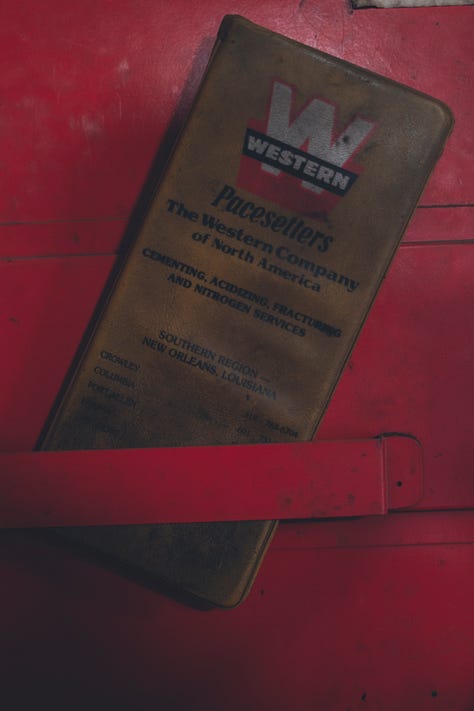

The place was a museum of grease and the smell of burnt motor oil, rows of wrenches, old motors on stands, half-drained coffee cups, and a radio that never played.

Mostly you heard the hiss of air tools and the sound of his boots scraping the concrete.

And up above the office rafters there lived a monster, the lapagator. It fed on loose bolts and bad behavior, or so he said. Every grandkid met it sooner or later. The air compressor would roar to life, rattling the tin roof, and we’d jump straight out of our skin. It was Grandy’s little ritual, his way of breaking you into the famly. You weren’t one of his grandkids until the lapagator had scared the tar out of you. He was as economically conservative as they came. He didn’t drink, didn’t borrow, didn’t waste words. He believed in hard work, the kind that left you bone-tired but honest. If you were lazy, he’d tell you plain. If you wanted something, you earned it. He wasn’t cruel, just carved by discipline. And to me, that made him the purest kind of man I knew.

But even the straightest boards have a warp in them, and every now and then something wild would shine through all that order. When I was thirteen, we rebuilt a truck together, a Ford with a 460 cubic inch motor that drank gas like it hated the ground it rolled on. No mufflers, long tube headers, just raw thunder.

We dropped that motor in with his old hoist and, when we fired it up, the hood trembled like it was afraid of heaven. The sound filled that little shop until the walls themselves seemed to hum. That truck was loud enough to make angels plug their ears, and maybe that was the point.

He handed me the keys when I was fifteen.

It wasn’t sensible.

It wasn’t prudent.

It sure wasn’t economical.

It was love.

It was the one place where my grandad let something unmeasured take over.

He lived his whole life by a code of cost and consequence, but when it came to engines, the numbers never mattered. Something in him, call it wonder, or beauty, or just the joy of a machine doing what it was made to do, broke through the rules he was so adamant about.

That’s what I want to talk about.

That tension.

Because my grandad, for all his work ethic and wisdom, carried inside him a contradiction I think a lot of us live with. The part that measures, and the part that marvels.

The part that keeps the ledger, and the part that burns it just to watch the light.

In a hot metal shop in West Texas, an old man made a boy believe that work was sacred and engines could sing.

On the Nature of the Economic Man

The economists have a name for a certain kind of man — homo economicus, the “economic man.” He is the one who calculates everything, who trades time for profit and love for gain, who believes life is a ledger and all things must balance.

He’s the creature who came to believe that reason is measured in utility and worth in productivity. When I think of that term, I picture a man like Grandy, though that’s not quite fair to him. He wasn’t greedy or cruel. He didn’t love money for money’s sake. But like many men of his generation, he had come to believe that the good life was a matter of order and efficiency, that if you worked hard enough and managed what you had, the world would make sense. It’s a sensible dream but a dangerous one. Homo economicus isn’t just an accountant’s idea. It is an ontological mistake, and that word “ontological” just means something has gone wrong at the level of reality. It is not that this man sins with his hands; it is that he misunderstands what a human is. He sees himself as a producer first, a consumer second, and a soul maybe somewhere down the line if there is time on Sunday.

One of my favorite philosophers Sergei Bulgkaov called it the idolatry of economy, the moment when the household of God becomes a factory run by man. What was once oikonomia, the divine care and ordering of creation, gets reduced to economics, a closed workshop of human will. The result is that the person, made to create as an act of communion, becomes a machine of accumulation. The modern world has confused the local with the national and the neighbor with the consumer. The world has become a market of lonely wills.

In West Texas, you can feel that machine even when you cannot see it. It hums beneath the oil fields and the subdivisions, in the push for growth and the fear of stillness. You are what you earn, what you build, what you own. And somewhere in all that striving, the sacred slips out the back door.

That is the tragedy of the economic man.

He works and builds and buys and sells, but he no longer knows what work is for.

He mistakes labor for purpose and profit for blessing. He wants control more than communion. And when a man trades communion for control, his soul starts to dry out like the West Texas desert.

Grandy never meant to teach me that lesson, but he did. In his love for self-sufficiency, I saw the limits of it. In that truck we built, I saw the hint of something better, a joy that could not be justified by utility. For just a moment, the balance of the bank account burned and what was left was grace.

“To own is to serve. Possession without service is theft from being.”

-Sergei Bulgkaov

To serve, is to live for the sake of another. It is to see every tool, every engine, every acre as part of a divine household, not as a collection of parts. That is what it means to live ontologically right, to see the reality of the world God has created. Not a world that is a market but one that is a communion. But we have built a culture that doesn’t see that truth. We have taught men to count everything except what counts. And the more we control, the less we belong.

That is the long shadow of homo economicus.

The Big Table

If the economic man is born in that shop in West Texas, his redemption begins at the table, not the metal workshop table, polished and cold, but the kind set for supper in his house. The one with the chipped plates and the passing of hands. The opposite of homo economicus is not the capitalist or the socialist.

It is the neighbor. The divine household.

The old theologians had a word for the world seen as one household — they called it cosmopolitan, from cosmos meaning world and polis meaning city. It did not mean fancy hotels it meant that all people and all things belong to the same house of God. To live cosmopolitan, in that older sense, is to live as if creation itself were a communion. Bulgakov said the true economy is not production but participation.

The world, he wrote, is God’s household, not our factory. Every act of work, of ownership, of exchange is meant to be a form of communion. When a man plants wheat or fixes a tractor or teaches his child, he is meant to be joining a divine rhythm, turning labor into liturgy. It is the recovery of the local, not as nationalism, but as a kind of cosmic belonging. The place where we remember that being itself is shared.

It is not fenced in by borders, hard work, how much money you have saved, politics, or brands. It is found in the faces that sit beside you, the soil you tend, the mercy you show. It is as wide and flat as the land in West Texas where the sky has no edge and every horizon seems to promise another. It runs deeper than any oil well or tribe.

The old book says, “The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it.” If that’s true, then every acre of pasture and every worn-out wrench already belongs to God. We just borrow them long enough to learn what serving means.

You don’t need a fancy degree to understand what I’m sayin, the land itself knows more than we do, for as Paul wrote, “The whole creation waits with eager longing to be set free.” You can hear it in the wind and the dirt that have learned to live together and through the mesquite groaning for the world’s redemption. You see it when the rain arrives as a gift, and when it falls, it falls on everything and everyone. The work, then, is to live as if the world were a table and not a marketplace. To see in each other not customers or competitors, but fellow servants of the same mystery. It sounds small, but maybe that is where all resurrections start. In the wine and the bread that sits on our table. If “in Him we live and move and have our being,” then all our moving and working, every turn of the wrench and every breath of dust, is already happening inside that grace.

I think about Grandy sometimes and I think he knew this deep down in his own way.

Maybe the reason he built that truck, loud and wasteful and glorious, was that he wanted me to feel something bigger. Without saying it, maybe he was showing me that work can be holy and that love is never efficient. His love was bigger than his economic values.

That is the task left to all of us, I think.

We are meant to take part in God’s own economy, not the kind measured in ledgers and markets, but the one written into reality itself. The old theologians called it the oikonomia theou — God’s household, God’s way of giving life. In that house, what is spent is never lost, and what is given away becomes more real. So, we build what does not make sense on paper. We give without measuring. We labor as though creation were still singing through the gears. That is the only economy that will last. That is the only economy that lasts forever.

Paul said it plain “For the present, faith, hope, and love remain—these three. And of these, the greatest is love.” That is God’s economy. The economy of love. The one that runs beneath all others, steady as a pumpjack in the distance, moving the world long after the markets have gone silent.